The Chinese and the Transcontinental Railroad

The Chinese, or Celestials (from the Celestial Empire), as they were often called in the 1800s, have a long history in Western America. Chinese records indicate that Buddhist priests traveled down the west coast from present day British Columbia to Baja California in 450 A.D. Spanish records show that there were Chinese ship builders in lower California between 1541 and 1746. When the first Anglo-Americans arrived in Los Angeles, they found Chinese shopkeepers.

Only a few Chinese were in the America's until gold was discovered in California in 1848. When news of the discovery reached China, many saw this as an opportunity to escape the extreme poverty of the time. Many peasant families were forced to sell one of their children, usually a girl, in order to survive. Paying $40 cash or signing a contract to repay $160 for passage, thousands were packed into ships for the voyage to the Golden Mountain as they called California. Lying on their sides in 18 inches of space, mortality ran as high as 25 per cent on some ships.

Unlike most immigrants, the Chinese didn't come to stay. All they wanted was to save $300-400 and then return to China to live a life of wealth and luxury. Three hundred dollars would allow them to marry, have children, a big house, fine clothes, the best foods, servants, and tutors for their children.

Opinions were mixed about these newcomers. The rich valued them as workers because they were willing to work for lower wages, were clean, dependable, did as they were told and didn't get drunk and fight at work. The working class feared that they would take their jobs. Discrimination was rampant. The Chinese could not become citizens, vote, own property, or even testify in court and had to live in certain areas of town and could only work at certain jobs. Life was hard, but by 1865, about 50,000 had come to the Golden Mountain.

After the Central Pacific (CP) started building the Transcontinental Railroad eastward from Sacramento, demand for Chinese workers increased greatly. The CP figured they needed 5,000 workers to build the railroad, but the most they ever had just using white workers was about 800. Most of these stayed only long enough for a free trip to the end of the track and then headed for the gold fields. The CP hired all the available Chinese workers and then sent agents to Canton province, Hong Kong, and Macao.

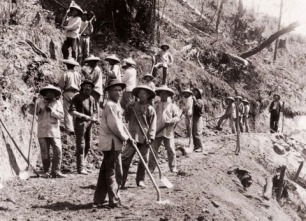

With an average height of 4'10" and weight of 120 lbs., many doubted these men could handle 80 lb. ties and 560 lb. rail sections. But handle them they did, as well as most other construction jobs. So well in fact that by the time they joined the rails at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869, more than 9 out of 10 CP workers, over 11,000 in all where Chinese.

Much of the work they did has become legend. Driving through California's Sierra Nevada Mountains, they were faced with solid granite outcroppings. After the CP's imported Cornish miners gave up, the Chinese with pick, shovel and black powder progressed at the rate of 8 inches a day. And this was working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, from both ends and both ways from a shaft in the middle. The winters spent in the Sierras were some of the worst on record with over 40 feet of snow. Camps and men were swept away by avalanches and those that weren't were buried in drifts. The Chinese had to dig tunnels from their huts to the work tunnels. Many didn't see daylight for months.

At Cape Horn in the Sierras, they hung suspended in baskets 2,000 ft. above the American River below them and drilled and blasted a road bed for the railroad without losing a single life (lots of fingers and hands though). After hitting the Nevada desert they averaged more than a mile a day. But working in 120 heat and breathing alkali dust took its toll. Most were bleeding constantly from the lungs.

Even though the CP --realizing how valuable they were-- treated them better than most, they were still not on a par with the whites. A white laborer was paid $35.00 a month plus room and board and supplies. The Chinese were paid $25.00 a month and paid for their own food, supplies, cook and headman. After a strike in the Sierras, where they won the right not to be whipped and beat and another strike in the Nevada desert, they got up to $35.00 a month but still paid for their own supplies.

The whites thought the Chinese were strange because of the strange clothes and hats they wore, because they ate strange foods and drank boiled tea all day, spoke in their sing-song language, and most of all, because they washed and put on clean clothes every day. The whites on the other had, drank from the puddles, seldom bathed or put on clean clothes, got drunk and fought and spent their hard-earned money on soiled doves and gambling.

In return for the dedication and hard work of the diligent Chinese laborers, an eight man Chinese crew was given the honor of bringing up and placing the last section of rail on May 10th, 1869. A few of the speakers mentioned the invaluable contributions of the Chinese but for the most part, the people of the day ignored them and history has neglected them. Only in the last 10-15 years has their story really started to become known. For the thousands who died aboard ship, the hundreds who died in accidents and the thousands who died of small pox it is long past due.

Golden Spike National Historic Site in Brigham City, Utah which was established in 1965, commemorates this history. On May 10, 1869, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Summit Utah and united the continent with the completion of the nation's first transcontinental railroad. Hence Chinese participation is prominent in what is perhaps the most important event in the history of the western expansion of the country. It linked East to West, opened up vast areas to settlement and provided easy access to new markets.

The Brown Quarterly

Volume 1, No. 3 (Spring 1997)

by Robert Chugg

Only a few Chinese were in the America's until gold was discovered in California in 1848. When news of the discovery reached China, many saw this as an opportunity to escape the extreme poverty of the time. Many peasant families were forced to sell one of their children, usually a girl, in order to survive. Paying $40 cash or signing a contract to repay $160 for passage, thousands were packed into ships for the voyage to the Golden Mountain as they called California. Lying on their sides in 18 inches of space, mortality ran as high as 25 per cent on some ships.

Unlike most immigrants, the Chinese didn't come to stay. All they wanted was to save $300-400 and then return to China to live a life of wealth and luxury. Three hundred dollars would allow them to marry, have children, a big house, fine clothes, the best foods, servants, and tutors for their children.

Opinions were mixed about these newcomers. The rich valued them as workers because they were willing to work for lower wages, were clean, dependable, did as they were told and didn't get drunk and fight at work. The working class feared that they would take their jobs. Discrimination was rampant. The Chinese could not become citizens, vote, own property, or even testify in court and had to live in certain areas of town and could only work at certain jobs. Life was hard, but by 1865, about 50,000 had come to the Golden Mountain.

After the Central Pacific (CP) started building the Transcontinental Railroad eastward from Sacramento, demand for Chinese workers increased greatly. The CP figured they needed 5,000 workers to build the railroad, but the most they ever had just using white workers was about 800. Most of these stayed only long enough for a free trip to the end of the track and then headed for the gold fields. The CP hired all the available Chinese workers and then sent agents to Canton province, Hong Kong, and Macao.

With an average height of 4'10" and weight of 120 lbs., many doubted these men could handle 80 lb. ties and 560 lb. rail sections. But handle them they did, as well as most other construction jobs. So well in fact that by the time they joined the rails at Promontory Summit, Utah on May 10, 1869, more than 9 out of 10 CP workers, over 11,000 in all where Chinese.

Much of the work they did has become legend. Driving through California's Sierra Nevada Mountains, they were faced with solid granite outcroppings. After the CP's imported Cornish miners gave up, the Chinese with pick, shovel and black powder progressed at the rate of 8 inches a day. And this was working 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, from both ends and both ways from a shaft in the middle. The winters spent in the Sierras were some of the worst on record with over 40 feet of snow. Camps and men were swept away by avalanches and those that weren't were buried in drifts. The Chinese had to dig tunnels from their huts to the work tunnels. Many didn't see daylight for months.

At Cape Horn in the Sierras, they hung suspended in baskets 2,000 ft. above the American River below them and drilled and blasted a road bed for the railroad without losing a single life (lots of fingers and hands though). After hitting the Nevada desert they averaged more than a mile a day. But working in 120 heat and breathing alkali dust took its toll. Most were bleeding constantly from the lungs.

Even though the CP --realizing how valuable they were-- treated them better than most, they were still not on a par with the whites. A white laborer was paid $35.00 a month plus room and board and supplies. The Chinese were paid $25.00 a month and paid for their own food, supplies, cook and headman. After a strike in the Sierras, where they won the right not to be whipped and beat and another strike in the Nevada desert, they got up to $35.00 a month but still paid for their own supplies.

The whites thought the Chinese were strange because of the strange clothes and hats they wore, because they ate strange foods and drank boiled tea all day, spoke in their sing-song language, and most of all, because they washed and put on clean clothes every day. The whites on the other had, drank from the puddles, seldom bathed or put on clean clothes, got drunk and fought and spent their hard-earned money on soiled doves and gambling.

In return for the dedication and hard work of the diligent Chinese laborers, an eight man Chinese crew was given the honor of bringing up and placing the last section of rail on May 10th, 1869. A few of the speakers mentioned the invaluable contributions of the Chinese but for the most part, the people of the day ignored them and history has neglected them. Only in the last 10-15 years has their story really started to become known. For the thousands who died aboard ship, the hundreds who died in accidents and the thousands who died of small pox it is long past due.

Golden Spike National Historic Site in Brigham City, Utah which was established in 1965, commemorates this history. On May 10, 1869, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads met at Promontory Summit Utah and united the continent with the completion of the nation's first transcontinental railroad. Hence Chinese participation is prominent in what is perhaps the most important event in the history of the western expansion of the country. It linked East to West, opened up vast areas to settlement and provided easy access to new markets.

The Brown Quarterly

Volume 1, No. 3 (Spring 1997)

by Robert Chugg